Being Governor of Jefferson has its particular perks, and its particular challenges. Particularly if you’re a member of this Pacific Northwest state’s most famous ethnic minority…with all the extra height and hair that implies.

Governor Bill Williamson of the state of Jefferson sat on the bed, waiting. He was ready to go. He had his shorts on, his wallet in one pocket, his keys in the other. That was as dressed-up, and as dressed, as he ever got. Several clean pairs of shorts sat in a small suitcase by the bed. Being a sasquatch made dressing and packing easier, one of the few advantages it had in a world dominated by little people.

Or he thought it made dressing up easier, anyhow. He looked at the bathroom door, which remained resolutely closed. He looked at the clock on the nightstand. What he saw made him mutter to himself. He looked at the bathroom door again. Still closed.

His patience slipped, which was dangerous for a politician and even more so for a husband. “Come on, Louise!” he called—bellowed, if you want to get right down to it. “We need to hit the road.”

“I’ll be out in a minute,” she said.

It was one of the longer minutes Bill had ever known. Impatient or not, he’d been married too long to say so. What he did say, when she came out in shorts much like his but a brighter blue and a matching top that covered and supported her breasts, was, “Whatever you did, it worked.” They’d had their silver anniversary the summer before. As husband and as politician, he knew how to keep people sweet.

Or he did most of the time, anyhow. All Louise said was, “Hrmp.” She didn’t like being noodged—a useful word Bill had picked up from Hyman Apfelbaum, Jefferson’s attorney general.

Getting up from the bed, he went over and hugged his wife. At nine feet two, he was almost two feet taller than she was; sasquatch genders differed in size more than little people did. “You’ll knock ’em dead in Ashland, kiddo,” he said.

“Save the soft soap for the head of the Appropriations Committee, okay?” she said tartly. But she couldn’t help smiling, and after a moment she relaxed in his arms and squeezed him back.

“Mike and I lie to each other all the time. It’s part of the game. I don’t play those games with you,” Bill said, which was largely true. Politics and marriage had different rules. Anyone who thought otherwise wouldn’t stay married, or in politics, long.

Louise picked up her own suitcase. It was bigger than Bill’s, but not a lot. “I’m ready. Let’s go,” she said. “It’ll be great to see Nicole.”

“It sure will,” Bill agreed. Their older daughter was a senior drama major at Jefferson State Ashland. Bill had no idea what kind of job she thought she’d get after she graduated, but he didn’t need to worry about that for another few months, anyhow.

Out the bedroom door he and Louise went. The doorways in the governor’s mansion were ten feet high; rooms had thirteen-foot ceilings. When Jefferson split off from Oregon and California right after the end of World War I, the first governor lived in a rented house. The new state’s treasury flush with Coolidge-era prosperity, the second governor built the mansion and the state Capitol. Charlie “Bigfoot” Lewis was a sasquatch himself, and had his architect run them up on a scale that suited him. His working assumption was that little people could deal with too big more easily than sasquatches could with too small. Bill blessed him every time he didn’t have to duck or bang his head.

The chief steward waited for them at the front door. Opening it, he said, “Enjoy your vacation, Governor, Mrs. Williamson. Give your daughter my best. She’ll be in. . . The Tempest, isn’t that right?”

“That is right, Ray,” Bill said, pleased the man had remembered. “I’ll tell her hello for you.”

Old Glory and Jefferson’s state flag flew on a tall pole in front of the mansion. Jefferson’s banner was pine green, with the state’s seal centered on the field: a gold pan marked with two X’s. They stood for the double crosses Jefferson had endured from Salem and Sacramento till its people finally got a bellyful and formed their own state.

After the War to End War, self-determination was all the rage in Europe. People in what had been southern Oregon and northern California grabbed it, too, grabbed it and ran with it. That neither Salem nor Sacramento was exactly broken-hearted to see them go didn’t hurt, either.

Bill’s car waited in the driveway by the flagpole. He fondly called the bronze 1974 Cadillac the Mighty Mo. It wasn’t quite the size of a battleship, but it came close. That was the last model year when Detroit could build for size without worrying about mileage. Then the first oil embargo hit, gas prices zoomed like a moon rocket, and cars got small faster than unpreshrunk jeans in a hot dryer.

The Mighty Mo was six years old now. It was getting elderly—cars aged faster than dogs. Bill aimed to keep it running as long as he could. He didn’t know of anything newer that could replace it. It guzzled gas the way a wino gulped muscatel, but what could you do? Economy and sasquatch size didn’t go together.

Bill dug out his keys and opened the trunk. It was big enough to hold a squad of little-people Marines. His suitcase and Louise’s vanished into its depths as if they had never been. The cavernous trunk seemed to say Is that all? Since that was all, Bill slammed the lid.

Then he opened the right front door and slid the right front seat as far forward as it would go. The Mighty Mo’s right front seat moved on a special track that let it slide forward a long, long way. Bill slammed the right front door and opened the right rear door. He waved Louise into the car. With the seat all the way forward, she didn’t fit badly. He closed the door. She locked it.

He walked around to the left rear door and got in himself. There was no left front seat. The Mighty Mo had an extra-long steering column so he or someone else his size could drive it. He stuck the key in the ignition and turned it. The enormous engine under that prairie of a hood rumbled to life.

“Ready to go?” he asked.

“Would I be sitting here next to you if I wasn’t?” Louise answered reasonably.

“Okay.” Bill put the Eldorado in gear, swung his size-32 right foot from the brake to the accelerator, and headed for the northbound onramp to the I-5.

Yreka had been the state capital for longer than he’d been alive, but it still wasn’t what anyone would call a big city. The governor’s mansion lay only a few blocks from the interstate. The Mighty Mo rolled past the Capitol and the state government office building next door to it.

The Capitol was splendidly neoclassical, with colonnades and a gilded dome. The office building was a Depression-era WPA special, square and ugly and functional. The wonder was that it had gone up at all. Gilbert Gable, who was governor then, did all he could for his home town of Port Orford and as little as he could get away with for Yreka.

Bill waited in the left-turn lane till he got a green arrow. Then his foot mashed the gas pedal again. The Cadillac zoomed forward. It was twice as heavy as a nice, economical compact car, but it had twice the motor, too. At least twice.

More and more of the cars that share the interstate with it were compacts, Datsuns and Toyotas and Hondas and Pintos and Vegas and Gremlins. They were a lot cheaper to run than the dinosaur-burning monster he piloted. He wouldn’t have minded having one himself, if only he could have driven it from anywhere forward of the trunk.

Hardly anyone on I-5 took the Federally mandated speed limit of fifty-five seriously. Bill sure didn’t. The Mighty Mo’s mileage was atrocious even at the double nickel. If it got a little worse at seventy or seventy-five, so what? He got where he was going sooner.

Signs on roadside fence posts and barns shouted for Ted Kennedy and Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan. The Jefferson primary was coming in a couple of weeks. Reagan already had the GOP nomination pretty much in his back pocket. Bill figured the ex-governor from one state south would have breezed here any which way. Jefferson’s Republicans averaged just to the right of Attila the Hun. Its Democrats, by contrast, were tree-huggers and left-over hippies. That made Kennedy the odds-on favorite.

From Yreka to Ashland was a little less than forty miles. The Mighty Mo had just passed from Siskiyou County to Jackson County–from what had been California to what used to be Oregon–when Louise said, “I don’t think Nicole’s happy about her part.”

“No?” Bill said. “She ought to be. She ought to be happy she’s got a part at all. The Ashland Shakespeare Festival gets to be a bigger deal every year. It draws more and more out-of-state tourists. It makes Ashland money. It makes Jefferson money. Sitting where I do, I can’t help liking that.”

His wife sighed. “I know, I know. She’s not happy anyhow.”

“She ought to be,” Bill repeated. “The festival gets more professional every year, too. They don’t usually let the Drama Department at Jefferson State put on a show any more. It’s not like it was in 1935—not even close.”

Jefferson State Ashland had started life as the Southern Oregon Normal School. It became the Ashland Normal School when Ashland and Oregon parted company, and went right on training teachers. One day in the mid-1930s, an instructor there named Angus Bowmer noticed that the roofless old building which had once housed Chautauqua lectures would do very nicely as an Elizabethan-style stage. Bowmer had always wanted to perform and to teach drama; he was training teachers because it was the Depression and you grabbed any job you could find and clung to it like a limpet.

The first few festivals were sort of like Ren Faires with plays. They included things like archery contests, bowling greens, and dances. Some of the actors were locals, others outsiders who odd-jobbed it while they performed. Nobody got paid, not at first.

It wasn’t like that any more. The festival had grown and grown. It went on without its founder, who’d retired in 1970 and died a year ago. It had its own campus now, not far from the state university, with three theaters, and ran from spring to fall. Jefferson State drama students still pitched in, but more often behind the scenes now than on stage.

Louise Williamson clucked, as if disappointed in Bill. “I understand all that,” she said—yes, she was unhappy with him. “It’s more complicated than you’re making it out to be, though.”

Or else Nicole’s taken arms against a sea of troubles that aren’t there, Bill thought, remembering Hamlet from his own high school and college English classes. Twenty-one-year-olds were good at that. They saw how many things were wrong with the world, and saw them very clearly. They didn’t see that fixing all those many things was usually harder than it looked. Bill hadn’t at twenty-one, either.

Ashland was a town of about 15,000: a college town and, this past generation, a Shakespeare town, too. Hotels and restaurants and shops catered to the outsiders who came to watch the plays. The locals who didn’t cater to tourists raised pears and apples and grain on the fertile soil of the Rogue River Valley.

They had reservations at the Columbia Hotel on Main Street, just a couple of blocks from the Festival campus. The Columbia was right next to the Varsity Theater, but that ran movies, not live drama. At the moment, the marquee plugged Mad Max and Gilda Live, which struck Bill as one of the odder pairings he’d run across lately.

One of the entrances into the hotel was tall enough for him to use without ducking very much, either. He didn’t have to walk through the lobby all hunched over, either. He’d been in the Jefferson State Senate when the Equal Accommodations Act finally passed in the early 1970s. If you ran a business in Jefferson, you had to do so in a way that let sasquatches—or yetis, or other oversized visitors—have access to it without turning into quasi-Quasimodos. Not all of it had to fit their needs, but some did.

Businessmen had fought the law all the way to the Jefferson Supreme Court. They’d lost. They’d lost in Federal district court, too, and at the Federal appeals level. If they took it to the U.S. Supreme Court, Bill expected them to lose there, too. Size was a civil-rights issue, dammit, just as much as race or gender.

The little man behind the registration desk smiled up at him and Louise. “Hello, Governor. Hello, Mrs. Williamson. “Welcome to the Columbia,” he said.

“Thanks.” Bill wondered whether ordinary sasquatches got the same kind of treatment he did. Remembering the days when he’d been on the road all the time selling real estate, he had his doubts. But he had the trappings and recognizability of rank now. He would till he lost an election. People would go on recognizing him even then. He wasn’t exactly inconspicuous.

He and Louise went through the rituals of checking in. He presented his American Express card. This trip was on his nickel, not Jefferson’s. “You’ll be in the Governor’s Suite—that’s room 111,” the desk clerk said. “Would you like me to ring for someone to take your bags?”

“No, that’s okay. Don’t bother.” Bill always declined such “favors.” He was so much bigger and stronger than anyone the desk clerk would call, having a flunky carry luggage for him seemed more an embarrassment than a service.

“Here you go, then.” The clerk handed him two keys. He gave Louise one. The clerk pointed. “It’s down that hallway and to your left.”

“Thanks.” Bill already knew that; he’d stayed at the Columbia on the campaign trail. But he appreciated the way the clerk worked to treat him like anyone else. Everybody got along in Jefferson, or at least tried. No one here gaped at him like a movie special effect, the way little men and women back East did when he traveled for a governors’ conference. (Some of the people who gaped most were other governors.)

The year before, the Yeti Lama, exiled since Mao’s soldiers overran Tibet and the Himalayas in 1959, had visited Jefferson. He wanted to see for himself how people of many races and sizes could lived together without murdering one another over differences in religion and politics and hairiness.

People here didn’t murder one another over such differences. . . these days. Bill hadn’t gone into detail about his state’s unfortunate past for the holy traveler. Well, damn few places didn’t have unfortunate pasts. Too many places, the Yeti Lama’s homeland among them, had unfortunate presents.

The door to Bill’s room suited a person of his size. The Columbia dated back to 1910; this was the Governor’s Suite because Bigfoot Lewis had stayed here back in the day. They didn’t need the Equal Accommodations Act to get with the program. Bill hardly minded bending a little to put the key in the lock. Sasquatches weren’t the only people who used the suite. You had to give to get.

Louise set down her bag and sat on the bed. She pulled a piece of paper from her purse. “Nicole’s number at the dorm,” she said. “I’m going to call her, let her know we’re here.”

“She’ll be glad to find out,” Bill said. “Mom and Dad are in town! No more dorm food for a while!”

“It’s not too awful, from what she says. And the meal plan. . . could be worse, anyhow,” his wife replied. Naturally, sasquatches ate more than little people. Just as naturally, university dorms expected them to pay more, too. Louise dialed the room phone. Actually, it was a modern one with buttons, and easier for her to use. She wasn’t that much bigger than little people; in a pinch, she could manage with a real dial. Bill had always needed a pen or pencil to deal with one of those. From force of habit, he still used one most of the time even on the push-button models.

This one was quite loud. From halfway across the room, he heard two rings and then a “Hello?” he thought was his daughter’s.

Sure enough, Louise said, “Hello, dear. We’re in Ashland, at the Columbia. Can you meet us at Gepetto’s at noon for lunch? You know—the place on Main, a couple of blocks down from the hotel.” She paused, listening. This time, Bill couldn’t make out what Nicole said. But Louise nodded. “See you then. ’Bye.” She hung up.

“Noon, huh?” Bill said. “Well, fine. And then I’ll hear the grand and gruesome story of why she isn’t happy with her part?”

His wife nodded again. “That’s right.”

“Oh, boy. I can hardly wait,” Bill said. Louise rolled her eyes. I know I can fib better than that, he thought. If I couldn’t, they never would have elected me to the State Senate, let alone governor.

He and Louise got to Gepetto’s ten minutes early. For Bill, that counted as right on time. He had a working politician’s horror of being late. It was as pleasant a morning here as it had been down in Yreka. They waited outside for their daughter to walk over from campus.

Standing there soaking up the springtime sun, Bill people-watched. In a college town, he remembered John Donne. No man is an island, entire of itself, Donne wrote. Any man’s death diminishes me, because I am involved in mankind.

Bill wanted to believe that, just as the old-time Englishman had. A pol who’d once sold houses and lots was, and needed to be, a gregarious soul. But Bill felt isolated in ways John Donne never could have imagined. Even in Jefferson, sasquatches were a tiny minority. Most people didn’t see them every day. Yes, staring was rude, but the sidelong glances he got instead might have been worse.

Then he smiled. He couldn’t help himself. Here came a pair of his own kind, walking down Main Street holding hands. They were both close to Nicole’s age. The boy wore an outsized baseball cap with JSA on the front, so they were college kids. They didn’t give a damn about feeling isolated, or anything else except each other. They walked past him and Louise without even noticing them.

They were lucky. They didn’t know how lucky they were, which was another way of saying they were young. Still smiling, Bill glanced down at the top of his wife’s head. Twenty-odd years ago now, he’d felt that way about her. He still did, even if experience tempered romance now. Louise wouldn’t know what he was thinking. She would have had her own dark moments down through the years. Man or woman, big or little, you couldn’t very well reach middle age without them.

She suddenly waved. “There’s Nicole!” she said. Sure enough, up Main Street from the direction of campus walked their firstborn. Being no more than an inch taller than Louise, she didn’t stand out that much from the little people around her. Jefferson’s settlers mostly came from northwestern Europe, and ran tall for their kind. Some of them also had a trace, or sometimes more than a trace, of sasquatch blood. For that matter, Bill thought—though he wasn’t sure—one of his great-grandmothers was a little person. Whether that story was true didn’t matter to him one way or the other.

Nicole waved back. She hurried toward them. Her last few steps were a trot. She hugged Louise and then Bill. “Sometimes I forget there are people as big as you, Daddy,” she said.

“Here I am, such as I am,” Bill said. “Sometimes I forget there are people bigger than I am. I was looking up to the Yeti Lama every which way last summer. He’s the only really holy person I ever met—and he’s six inches taller than me.” Maybe that had to do with the great-grandmother he’d never met. Maybe yetis averaged taller than their North American cousins. Or maybe the Yeti Lama was just a great big fellow and Bill not so much.

His daughter pointed toward Gepetto’s front door. “Let’s eat,” she said. “They do pretty good burgers, and their wontons are great.”

“Works for me. I bet I could eat one ton of them all by myself.” Bill pronounced the weight so it sounded like the Chinese dish. Louise and Nicole both groaned. They knew that, tall as he was, he had a low taste for puns. He had to work hard not to let it out where it could alarm his constituents.

“Governor Williamson!” exclaimed the middle-aged woman at a lectern who seated people. “You’ll want a table set up for big people, won’t you?”

“Yes, please, if you have one,” he said.

“We sure do. Right this way.” She scooped up menus and led them to a table and chairs that suited their size. No trouble with the Equal Accommodations Act here—and Bill wouldn’t need to worry about where to put his knees.

The waitress who took their orders was short even by little-people standards. Bill needed a moment to notice that; all little people, even basketball players, seemed short to him. He saw she was cute right away. Living in the wider culture his whole life made him as much aware of attractive little-people females as his own kind. He was happy with Louise, so he’d never done anything more than notice. The waitress’ head hair almost matched his own russet pelt, which was interesting and uncommon among her kind.

When the food came, they spent a while giving the hamburgers and wontons and fries and shakes the attention they deserved. After a while, happily replete, Bill asked, “How’s the play coming along?”

Louise shot him a warning glance. Like most such, it arrived too late. Nicole’s face clouded over. “Pretty bad,” she said. “You know I’m one of the best at the school.”

“Uh-huh.” Bill nodded. He did know that. Quietly and without any fuss, he’d made it a point to find out. He also knew it would do his daughter less good than she hoped once she left the friendly confines of Jefferson State Ashland. He ate a few more french fries. Then he said, “So?”

“So we’re doing The Tempest, right?” Nicole spoke to him as if sure he was none too bright: the tone that always did so much to endear the rising generation to its elders. “So I was hoping they’d cast me for Miranda. But the director isn’t a JSA guy. The Shakespeare Festival brought him in—he’s from Pittsburgh, for crying out loud.” She stopped, too disgusted to go on.

“So what part did he give you?” Bill asked, fearing he knew the answer before he heard it. And he did.

“Caliban!” His daughter spat out the name with so much venom, several little people’s heads whipped around. In a slightly—but only slightly—softer voice, she went on, “Talk about stereotyping! My God!” She made as if to clap her hands to her head. But her fingers were greasy, so she didn’t.

“You see what I mean,” Louise said.

Bill nodded unhappily. “Who’s playing Miranda, then?” he asked.

“Jackie van Herpen,” Nicole replied.

“She any good?”

His daughter turned her right thumb toward the floor. Vespasian couldn’t have done it with more imperial hauteur. She said, “I suppose she’s pretty, if you like brainless blondes.”

Some men, little and big, did. Quite a few, in fact. Bill found another question: “Is the guy from, uh, Pittsburgh sleeping with her?”

For the first time since naming Shakespeare’s mooncalf, Nicole smiled. “I don’t think so,” she said. “He’s gay as gay can be.”

“Okay. Good, even.” Most of the time, Bill didn’t care who went to bed with whom, or why. But if the director was balling his Miranda, no way in hell he’d change his mind about casting. Since he wasn’t, he might—possibly—listen to reason (which, to Bill, meant doing what he wanted). “What’s his name, and how do I get hold of him?”

“He’s Reggie Pesky, and he’s at the Angus Bowmer Theatre, the small one—that’s where we’ll perform.” Nicole suddenly looked anxious. “Maybe you should call over there and meet him somewhere else. Out of his territory.”

Bill nodded thoughtfully. “That makes sense, but I’ll do it anyway.” Nicole stuck out her tongue at him. He went on, “Remember, just because we talk, there’s no guarantee of anything. All I can do is try.”

“I know, Dad.” Nicole sounded confident, though, and why not? Wasn’t her father nine feet tall (and then some)? Wasn’t he governor of Jefferson? Didn’t all that mean he could do anything?

As a matter of fact, no, Bill thought. Nine feet tall or not, he was only human. And a recalcitrant Legislature had taught him a governor could only do so much. Of course, Reggie Pesky was a theatre guy, not a politician. He might not grok that. If he didn’t, Bill had no intention of enlightening him.

Sitting in a sasquatch-sized chair in the Columbia’s lobby, Bill pretended to read the Ashland Daily Tidings. In fact, he barely noticed the words on the newsprint. He’d spent the afternoon at a different kind of reading. He hadn’t dug into Shakespeare since English Lit in college. He wondered why not. The old boy knew a trick or three, sure as hell.

Reggie Pesky walked in at six o’clock sharp, on time to the minute, which made Bill think well of him. He recognized the little man at once from Nicole’s description: longish yellow hair, blue eyes, very pale skin, broad cheekbones, snappy clothes. Bill would have bet dollars to dimes the director hadn’t been born with the moniker he used these days. By his looks, something on the order of Riszard Paweskowicz seemed more likely.

But that had nothing to do with the price of beer. Bill stood up. He wanted to intimidate a bit, or more than a bit. Pesky was fair-sized for a little man; he stood close to six feet. That put his eyes on a level somewhere near Bill’s diaphragm.

“Hello, Mr. Pesky. Thanks for coming by.” Bill’s voice, deeper than deep, was another polite weapon. He held out his hand. The way it engulfed the director’s was one more.

“I’m delighted to meet you, Governor Williamson. Your daughter is very. . . impressive. You’re even more so.” Reggie Pesky stared at his hand as if delighted to get it back again.

Bill didn’t think Nicole was wrong about which way he swung. “Call me Bill,” he said. “I’m just trying to get along, same as anybody else.”

“Then I’m Reggie, of course,” Pesky said.

“Shall we get something to eat? The restaurant’s pretty decent—I’ve stayed here before,” Bill said. His wife and daughter would have dinner somewhere else. Bill wanted to talk to the director with his governor hat on, not his daddy hat.

In they went. As at Gepetto’s, a couple of tables were large enough to let sasquatches eat comfortably. A busboy brought Pesky a tall chair so he could sit at one with Bill, the way a child would have got a booster seat at a regular table. The expression on the little man’s face was a caution.

Reggie Pesky ordered a Bombay Sapphire and tonic, Bill a triple scotch. He liked beer better, but he needed half a gallon for a buzz. Pesky raised a pale eyebrow. “Your bar tab must be hell,” he said sympathetically.

“Now that you mention it, yes,” Bill agreed. “My grocery bill, too. Being big ain’t all it’s cracked up to be.”

The director hoisted his eyebrow again, in a slightly different way this time. Bill thought he knew what that meant. Gay sasquatches from Jefferson had joined their little brethren in the move to San Francisco. Their. . . attributes were in great demand among a certain set there. A rather smaller set of little women admired straight sasquatches for similar reasons.

When the drinks came, Bill and Pesky clinked glasses. Bill savored his smoky single malt. “I’m so glad I came to Jefferson,” Pesky said. “This is the first chance I’ve had to work with sasquatches. Yunz are remarkable people.”

“Yunz?” Bill wondered if he’d heard right.

“Did I just say that?” The director looked astonished at himself. He seemed to play a tape back in his head, because he sighed. “Good God, I guess I did. It’s. . . Pittsburgh for y’all, is what it is. They call people who talk that way yunzers. My folks sure as hell did—do—but I thought I outgrew it years and years ago.” He laughed and sipped his drink. “Shows what I know, doesn’t it?”

“We’re more like other people than we’re different,” Bill said.

“Well, I tell people the same thing, and most of the time it’s true,” Pesky replied. He, no doubt, wasn’t talking about his size or how hairy he was. Bill nodded anyway. Reggie Pesky went on, “Sometimes it isn’t, though. Sometimes the differences matter.”

Before Bill needed to answer that, the waitress came up and said brightly, “Would you gentlemen care for another drink? And are you ready to order, or do you need another few minutes?”

Bill looked a question at the director. Pesky bobbed his head up and down. “I’d like another drink, yeah,” Bill said. “And I’ll have the sasquatch-sized prime rib, rare.” Reggie Pesky ordered a fresh gin and tonic and broiled salmon.

“Thank you.” The waitress beamed at them. “I’ll bring the drinks right away, and I’ll have your dinners for you as soon as they’re up.” Bill watched her backside work when she hurried away. Pesky forgot about her as soon as she wasn’t standing there any more. Sure enough, there were differences, and then there were differences.

The drinks came as fast as promised. Reggie Pesky smiled when Bill sipped from his. “I’d fall over if I had two that size,” he said.

“There are little men who drink more than I do,” Bill said. “Some of the old-timers in Yreka. . . They start putting it away right after breakfast, and they quit when they go to bed. You never see ’em falling-down drunk, though. They just go along like that, full of antifreeze—”

“Till their liver conks out,” Pesky put in.

“Uh-huh. Or till lung cancer or emphysema gets ’em, ’cause they mostly smoke like chimneys, too.”

Pesky grinned crookedly. “We’re cheerful, aren’t we?”

“Oh, at least,” Bill said, which made the little man chuckle. The governor added, “And here’s the chow.”

Up strode the waitress, a large tray on her left shoulder. With the deftness of long practice, she supported the tray with her left hand while using her right to set plates on the table. “There you go,” she said. “Do you need anything else right now?”

“Don’t think so,” Bill said. She lowered the tray and hustled off to whatever she had to do next.

Reggie Pesky eyed Bill’s slab of prime rib with undisguised admiration. “They got all of that from one cow?” he said.

“Looks like it.” Bill cut off a bite, dipped it in the au jus, chewed, swallowed, and smiled. “A cow that died happy, too.”

About halfway through dinner, Pesky paused and said, “I just wanted to let you know what a pleasure it is working with your daughter, Governor.”

Bill had heard that tone of voice before. It was the tone of a man who knew which side his bread was buttered on. Bill said, “That’s part of the reason I invited you to dinner tonight.”

“I thought it might be,” the director said. No, he was no dope. Well, he wouldn’t have the slot he had if he were. He continued, “She understudies Miranda very well. I’ve been impressed. I know I said that before, but she has talent.”

“Thanks.” Bill picked his words with care: “If she’s so good, why didn’t she get the part?”

Reggie Pesky looked at his drink and seemed disappointed to find it empty. “A couple of reasons,” he said after a moment, also plainly thinking about what came out of his mouth. “Probably the most important is that here in Jefferson I have a chance I probably never would anywhere else—the chance to do The Tempest with a Caliban who doesn’t need makeup.”

“What makes you say that? Caliban’s not a sasquatch. Shakespeare never heard of sasquatches. We hadn’t run into white people yet,” Bill said. “Caliban’s a cross between a woman and a devil. He can look like anything you want him to. Saying he looks like a sasquatch, isn’t that the worst kind of typecasting?”

Pesky blinked. “I never dreamt you—or Nicole—would take it like that. It’s not how I meant it.”

The alarming thing was, Bill believed him. “You know, I think you could get away with that kind of casting in Boston or Philadelphia, maybe even New York.” He made a point of not mentioning Pittsburgh. After a bite from one of his baked potatoes, he continued, “This is Ashland, though. Little people here are used to sasquatches. They see them all the time. They take them for granted, as much as they do with, say, black people or Vietnamese.” He exaggerated, but by less than he would have anywhere else in the country.

“Mm.” Reggie Pesky also did some eating. If he needed time to think, Bill would give it to him. Pesky blotted his lips with his napkin. He was very neat, very precise. “There is also a certain difficulty with suspension of disbelief, you know.”

And with that they came down to it, as Bill had guessed they would. “I’ve got two things to say, Mr. Pesky.” So much for first names. “The first one is, it’s called acting. You must have seen the movie with Olivier playing Othello.”

“Oh, sure.” The director nodded.

“Does he look like a Moor to you?”

“He looks like Olivier with shoe polish on his face.”

Bill laughed. “Okay, we’re on the same page. Is it a good performance?”

“If you like chewing the scenery the way the Brits did a generation ago, maybe.” Pesky realized he couldn’t stop there. He grudged a nod. “Yes, it’s a good performance.”

“All right. The other thing is, you don’t believe Nicole can make people believe she’s Prospero’s daughter?”

“It’s. . . a stretch,” Pesky said.

“Says you. The thing is, Prospero may honest to God be the kid’s three-times-great-grandfather.”

“Run that by me again?” the director said.

“There’s a family story that says one of my great-grandmothers—Nicole’s great-great—was a little woman. I don’t know that that’s true, but I don’t know that it’s not, either. A lot of sasquatches here in Jefferson have little people in the woodpile, and the other way around. And I have no idea who great-granny’s father was. Maybe it was Prospero, if his revels weren’t then ended.”

“A lot of people, I’d think they were making that up to bullshit me,” Pesky said. “I believe you. Don’t know why, but I do.”

Life’s too short for bullshit. Bill believed that. He didn’t think Pesky would believe him. And, just because he disliked bullshit, that didn’t mean he didn’t use it now and again. It was an indispensable lubricant in the working politician’s toolbox.

He tried a different tack instead: “How good is the girl you’ve got doing Miranda now?” He knew what Nicole thought of Jackie van Herpen. He also knew his kid might not be completely objective.

“She’s okay.” Pesky might or might not be praising with faint damn. After glancing around to make sure no one but Bill could hear, he went on, “Miranda should be pretty, and Jackie’s what they call a double-breasted mattress-thrasher. Most of the guys in the audience will notice.”

The they and the most distanced him from the people he was talking about. Bill felt even more distanced himself. To little people, and especially to little people who weren’t used to them, sasquatches’ size and hairiness and heavy features were off-putting, to say the least. Nicole was a fine-looking girl. . . if you had the eyes to see it. A gay little man from Pittsburgh wasn’t likely to.

“This is Jefferson, you know,” he said, going as far as he thought he could in that direction without getting offensive. “Audiences here don’t look at things the way they do where they haven’t grown up with us.”

Maybe he went too far anyway. “Mr. Williamson, if you were a sasquatch who sold shoes or drove a truck, you’d never have the nerve to rattle my cage about casting,” Reggie Pesky said. “Because you’re governor, you think you can throw your weight around, the same way you would if you were a—what do you say?—a little man. Some things don’t change, do they?” He put a twenty on the table. “Even at hotel prices, this’ll cover mine and the tip. See you.” He slid off the tall chair and walked away.

Bill scowled after him. Little people made the same jokes about sasquatches as they did about gorillas. They didn’t make them where sasquatches could hear—not more than once—but he knew about them. Where does the 500-pound sasquatch sit? Anywhere he wants to. Bill nodded to himself. Five hundred pounds was just about what he tipped the scales at. He had a lot of weight to throw around.

Jerry Turner had succeeded Angus Bowmer as producing director for the Ashland Shakespeare Festival in 1971. He wasn’t a native, but he’d started performing at Ashland in 1957. He’d taught drama down at Jefferson State Arcata till he took the slot here. If anybody who wasn’t born in Jefferson got how things here worked, he was the man.

If anyone did. All Bill could do was find out—and play a little politics while he was at it.

He guessed Turner was five or ten years older than he was himself. The producing director had a cramped office in the festival’s administration building near the Bowmer Theatre. It seemed all the more cramped with Bill in it. “Are you all right, Governor?” Turner asked with what sounded like real concern. “We can talk outside if you’d rather.”

“Don’t worry about it. You were kind enough to get a chair that fits my big old behind, and to see me early in the morning,” Bill said. The ceiling here was just about tall enough, but he felt as if the walls were closing in on him. From long practice, he shoved that out of his mind. Sasquatches dealt with claustrophobia all the time. In a world with a few of them and swarms of little people, they had to.

“When the governor says he wants to see me, he can see me,” Turner answered. “I suspect I have some idea of what this is about.”

“Do you?” Bill said, unsurprised. “Reggie Pesky talked to you?”

“He called last night, yes,” Turner said. “He was. . . a little bent out of shape.”

“He doesn’t quite see what Jefferson is like,” Bill said. “Or that’s how it looks to me, anyhow. You’ve got a sasquatch in your troupe? What’ll she play? Caliban! Talk about typecasting! Talk about stereotypes! C’mon—you’ve been here a long time now. Is that what you want the Ashland Shakespeare Festival to stand for? It’s not what this state’s all about.”

Jerry Turner steepled his fingers as he thought. As befit someone who ran things, he didn’t shoot from the lip. “It bothers me, too,” he said at last. “But when I invite someone to come here and work with our people, I’m reluctant to second-guess him. Otherwise, it turns into my play, not his—and next year I’ll have trouble finding anyone who wants to work with me.”

“I understand that,” Bill said. “But when somebody plainly hasn’t got a clue—”

“Can you give me an example of what you mean?” Turner interrupted. “No offense, but I do want to make sure you’re not just a parent bitching about the part his kid got.”

Bill was a parent bitching about the part his kid got, but he hoped he wasn’t just that kind of parent. “I sure can,” he said. “Last night, he told me he was glad Nicole was in the troupe because she could play Caliban without any makeup.”

Turner’s mouth puckered as if he’d bitten into an unripe persimmon. “Oh, dear,” he said.

“Uh-huh.” Bill nodded. “If that’s not clueless, I don’t know what is. He looks at a sasquatch, and all he sees is a funny-looking critter. He doesn’t see an actor. He doesn’t see how there can be an actor under the fuzz, if you know what I mean.”

“That kind of thing won’t make the reviewers happy. Not in Jefferson. Not in Ashland,” Turner said fretfully. Bill smiled, but only inside, where it didn’t show. He’d hit the producing director where he lived. Turner went on, “The festival grows out of what the state is. If we’re about anything, we’re about giving people chances because of what they can do, not because of what they look like.”

“Feels the same way to me.” Bill had come to see Jerry Turner with a carrot as well as a stick. He said, “The Ashland Shakespeare Festival’s brought Jefferson credit for a long time. Even before the war, the state WPA Guide talks about it.”

“Yes, I know—and it calls Angus Bowmer Angus Bowman,” Turner said with a grin. “He used to laugh about it and say, ‘Fame is getting your name spelled wrong in the history books.’”

“I like that,” Bill said. “So anyway, I was thinking maybe it’s time to change the name of what goes on here from the Ashland Shakespeare Festival to the Jefferson Shakespeare Festival, and to put in a little state money to help things grow and move along.”

“No strings attached?” Turner asked.

“How do you mean?”

“A couple of years ago, the National Endowment for the Arts offered us a $50,000 grant, but we had to sign a pledge that we wouldn’t do anything obscene. We said thanks but no thanks.”

“Jerry, I don’t give a damn what you do with the money, as long as you don’t frighten the horses,” Bill said.

The producing director didn’t ask how much money the governor was talking about. That was good. It showed a certain amount of trust. And Bill knew too well that some primitives in the Legislature threw nickels around as if they were manhole covers. But he was pretty sure he could get this through. Hardly anyone in Jefferson wasn’t proud of the Ashland Shakespeare Festival.

What Turner did say was, “Well, I’ll talk with Reggie about reconsidering. He may frighten the horses when I do, but I’ll make it work.”

“Thanks. Thanks very much.” Something else occurred to Bill: “I hope you can get the programs fixed in time for opening night.”

“We won’t print new ones. That would cost way too much,” Turner replied. “We’ll do inserts instead. But they’ll look good, promise. We got ourselves a Wang word processor last year. It’s crazy—It’s a computer that sets type. I don’t know what we’d do without it.”

“I’ve seen ’em. State government’s starting to use ’em, too,” Bill said. “They’re amazing, all right. Who knows what they’ll come up with next?”

“Yeah.” Jerry Turner nodded. “Who knows?”

The usher smiled up and up at Bill and Louise. One of the nice things about handing out programs before a play was the interesting people you met. “Hello, Governor. Hello, Mrs. Williamson,” he said. “The sasquatches’ box is on your left, down at the front. I hope you enjoy the show.”

“I’m sure we will,” Louise said, beating her husband to the punch.

Bill opened his program and looked through it as he and Louise walked to their seats. Sure enough, the insert did look good. It was on the same coated stock as the rest of the booklet, and the typeface matched, too. They could do wild things these days, all right.

He took a step down to the sasquatches’ box. The floor there was lower than in in the rest of the Angus Bowmer Theatre, so big people could get down close without blocking the view of the little folks behind them. Another couple was already in the box. Bill didn’t know them, but they looked familiar. A moment later, he realized why. They were the college kids who’d walked by when he and Louise were waiting for Nicole outside Gepetto’s.

They realized who he was at about the same time. Both of them bobbed their heads at him—the guy wasn’t wearing his JSA cap now. He said, “That’s your daughter in the show, right?”

“Yup.” Bill beamed.

“How cool is that?” the girl said.

“Do you know Nicole?” Bill asked. Sure enough, they did. He’d figured they would. Sasquatches stuck out from the crowd of little people. The two couples chatted till the house lights dimmed.

The Tempest’s opening scene, out on the ocean, was all Sturm und Drang—literally. Kettledrums supplied the thunder, as they would have in Shakespeare’s day. Lasers blazing through dry-ice smoke did duty for stormclouds and lightning. Reggie Pesky knew more staging tricks than were dreamt of in the Bard’s philosophy. As their ship foundered, the men in it took to the boats.

Act One, Scene Two was set in front of Prospero’s cell on the island where the main action took place. Bill tensed when the young little man playing Prospero—decked out in a gray wig and a pretty good fake gray beard—and his own daughter as Miranda entered. A couple of murmurs rose from the audience, but no angry shouts and (he thanked heaven) no laughter. Much of the crowd would be from Jefferson, used to sasquatches and used to suspending disbelief for them if a performance rated it. The out-of-staters seemed willing to roll with things for a while, anyhow.

“‘If by your art, my dearest father, you have/ Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them. . . .’” Nicole went on with Miranda’s first speech. She had the words down, and the feelings behind them. Her voice was deeper than a little woman’s, but she didn’t sound like a little man, either. She sounded like—herself.

That scene filled the rest of the first act. Ariel’s tight-fitting costume was covered with thin diffraction-grating disks that gave off rainbows whenever the girl playing the spirit moved. Caliban looked more like a lumpy alien from the Star Wars cantina than a sasquatch. Bill hadn’t pictured the semihuman that way, but the makeup didn’t set his teeth on edge.

Bill’s other anxious moment came in the last act, when Miranda exclaimed, “‘Oh, wonder!/ How many goodly creatures are there here!/ How beauteous mankind is! Oh, brave new world,/ That has such people in ’t!’”

By then, though, Nicole had done well enough so the audience took her for granted in the role. More than that, she couldn’t hope. Well, she could hope—it didn’t hurt. Whether she hoped or not, though, Bill didn’t expect the Royal Shakespeare Company to call any time soon. Good as she was, Nicole wasn’t that good. Stratford-on-Avon wasn’t Jefferson, either.

He blistered his palms when the cast came out to take their bows. His daughter got as big a hand as he thought she deserved. He felt about to burst with pride.

In spite of the Equal Accommodations Act, when Bill went backstage he had to walk carefully to keep from bumping his head on the ceiling. Nicole’s dressing room barely held three sasquatches. “I did it!” she kept saying. “Oh, my God! I really did it!”

“You sure did,” Bill said. “You were great, too.” That might have stretched things a bit, but people who told the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth to their nearest and dearest soon found themselves not so near and not so dear.

After a bit, Louise tugged at his arm. “We shouldn’t hang around,” she said. “We can talk more later. She still has stuff to do.”

“I suppose so,” Bill answered grumpily, knowing she was right. When he opened the dressing-room door to go out, he almost ran into—ran over—Reggie Pesky coming in.

“Hello, Governor,” the director said with a sour smile. “I was hoping you’d come back. I have a couple of things I want to tell you.”

“Go ahead. I’m listening,” Bill said.

“The first one is, that worked better than I thought it would. Your daughter did a nice job, and the audience bought it.”

“Okay, that’s one. What’s the other?”

“Fuck you. Just. . . fuck you.”

Bill could have driven him into the ground like a nail. People would have talked if he did, though. “Don’t worry about it, man,” he said after a beat. “I love you, too.”

“Are you ready, Governor?” his publicist asked. A blonde with a nice shape, Barbara Rasmussen was almost too decorative for the work she did.

Bill took his place behind the massive gubernatorial desk. Once Bigfoot Lewis’, it had sat in storage for years and years, till in their wisdom the people of Jefferson chose another sasquatch to lead them. He made sure the bill on the desk was the one he was supposed to be signing. He also made sure the pen he’d sign it with wrote.

The bill was the right one. The pen did have the right stuff. The governor nodded. “We’re good to go. You can let ’em in.”

Barbara opened the door to the governor’s study. Reporters and still photographers came in. TV cameramen took their places at cameras already set up and waiting for them. Barbara turned a rheostat. The lights above the desk got brighter—and hotter. Bill started to sweat.

“Governor Williamson will make a brief statement,” Barbara said, telling the press corps what they already knew. “Then he’ll sign the bill, and then he’ll take a few questions.”

As soon as the red lights under the camera lenses went on, Bill smiled at them and said, “hello folks. We all know the Ashland Shakespeare Festival has helped put Jefferson on the map since the Depression was at its worst. I’m proud that our state has America’s first Elizabethan theatre. And, under the new producing director, Jerry Turner, the festival has grown in size and scope. It draws coverage from around the world, and it draws lots of visitors to Jefferson.

“Because of all that, the Legislature and I have agreed it’s high time our state recognizes how important the festival is. The bill I’m going to sign today changes its name from the Ashland Shakespeare Festival to the Jefferson Shakespeare Festival. And, to show we’re putting our money where our mouth is, the bill authorizes an annual state grant of $75,000 to the festival to support it and help it expand even more.”

He’d wanted to give the festival $150,000 a year. He’d expected the tightwads in the Capitol to haggle him down to a flat hundred grand. They proved even tighter than he’d figured on, though. One of the things politics was was the art of taking what you could get. Otherwise, you ended up with nothing.

Bill ceremoniously picked up the pen and signed three copies of the bill as the TV cameras followed his every move and the still photographers flashed and clicked away. Then he waved to the reporters, inviting the questions Barbara had promised.

“What kind of strings go with the money?” asked the man from the Port Orford Post.

“Well, Pete, the usual financial kind, to make sure the people in Ashland only spend the grant on things that have to do with the festival. Jerry Turner won’t head for the closest Bentley dealership with the check.” Bill got a few chuckles. He went on, “Of course, if I thought he’d do anything like that I wouldn’t have proposed the bill in the first place. And there are no artistic strings attached.”

“None?” Pete said.

“None,” Bill echoed. “This is Jefferson. This isn’t a place where we give with one hand and take away with the other. This isn’t a place where we tell people how to do things. This is a place where we let them do things. If you don’t like what they do, you don’t have to go. We got to be a state by doing our own things here. We’ve been doing it ever since, long before the hippies latch on to the phrase.”

“Did your daughter being in a Shakespeare play have anything to do with this grant?” the reporter from the Ashland Daily Tidings asked.

“Maybe a little something, Annie.” Not usually someone given to understatements, Bill paused a moment to admire that one. Then he continued, “She certainly helped put Ashland on my radar, and the festival deserves all the help we can give it.”

“Her casting changed at the last minute,” Annie said. “Did that have anything to do with what you just signed?”

Bill shrugged his wide, wide shoulders. “I have no artistic control over the festival. I don’t want any, either. I’d just foul it up. I will say I’m a proud papa like any other proud papa.”

If any or any other people wanted to push it, they could raise a stink. Reggie Pesky would likely be glad to lend a helping hand. But no one seemed eager. It was a feel-good bill. It was a feel-good story. Why mess with it?

A few more harmless questions followed. Then the reporters and photographers hurried out of the study to get their stories and pictures in. Bill leaned back in his swivel chair. It creaked.

“That went fine,” Barbara remarked.

“Yeah, I think so, too,” Bill said. “And all’s well that ends well.” He winked.

“Typecasting” copyright © 2016 by Harry Turtledove

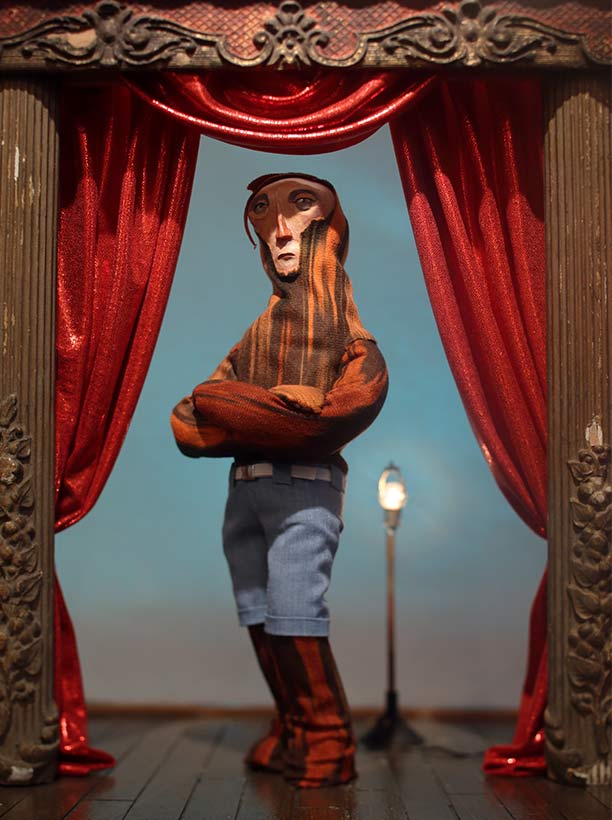

Art copyright © 2016 by Red Nose Studio